LOUISIANA PURCHASE

Chapbook Reviews

Review of Louisiana Purchase a Chapbook by Elizabeth Burk

December 2, 2014 by Angelina Oberdan

Here, in Charlotte, North Carolina, early winter is grey with rain and clouds and cold. And something about the color

of the sky makes me miss Louisiana. I picked up Louisiana Purchase by Elizabeth Burk (Yellow Flag Press 2014), and while

I hoped that it would quell my craving for roux-based poetry, I did not know how fully it would suit.

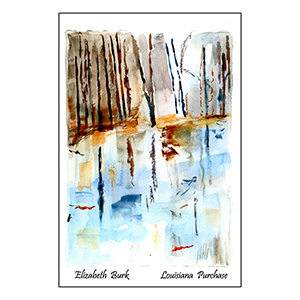

Louisiana Purchase is a sturdy sixteen-poem collection. Like all chapbooks from Yellow Flag Press, it is printed on

cardstock and high-quality paper, bound by staples, and carefully edited. The watercolor print on the front cover

reminds me of both the snow-filled forests of New York and the winter-brown bayous of Louisiana: the two places of the poems.

As the author is (she lives between New York and Louisiana), this collection is composed in two places. The first

section of this series focuses on the speaker, her husband (I assume based on biographical information), and his going

to and coming from Louisiana. For example, in “Snow Day Up North,” Burk writes about her husband being delayed:

your flight back has been delayed

house grows colder, emptier.

I slide sideways into town on icy roads

In this poem, she becomes an Estonian snow queen, and although her heart is frozen,

I like how she claims the storm and its associated emotions.

If the aforementioned leaving of New York for Louisiana is the narrative of these poems, I can’t stop thinking about one of the poems that breaks it. There are two poems, one in each section, that are about the speaker’s old lovers, but the first appearance of an old boyfriend is never reconciled like the second one is with an equal (and much more macho) image of her husband (“Endangered Species”). And isn’t this true? Isn’t it when our partner demands something of us that we want to give but aren’t sure we can that those old lovers seem to appear? The poem, “Upon Hearing Your Ill,” is about just that, and seems filled with the regret for this love the speaker never quite returned. Burk writes,

I went on to do

what you had warned against,

married for less than love, afraid

my time was running out.

I saw you occasionally after that

at major crossroads in my life.

That is to say, every time you appeared

life either changed

or stayed the same.

To think of you now, aging and ill,

being helped to the stage,

struggling to read your own words,

I see that our dream of traveling

to Damascus is finally, forever

out of the question.

While the speaker cannot and will not join this former love on a trip they once dreamed to take together, she will go to Louisiana with her husband, no matter how uncertain it feels in poems like “How Can I Leave.”

Interestingly, and to my pleasure, if the New York poems of the first section are filled with an insider’s understanding, the Louisiana poems of the second section are not those threaded with the cautious scorn of an outsider. Rather, they are very true to my experience of Louisiana. While I would have bought the “Cotton Gin” that the speaker and her husband decline purchasing, “Bayou Country” is a quintessential Louisiana poem whose form mimics the edge of the bayou. Burk writes, “Cypress knees poke / through rivers, pirogues / drift, break the surface / where mirrored limbs hang heavy with / slippery moss, float / like ancestral ghosts.” The images in this poem and the sounds of the words move like a bayou: slow and thick.

While in the second section of Louisiana Purchase fills my gumbo craving, I also found a speaker who claims both places she lives and loves. The poem “Needing Green” ends:

I wanted banana trees with bottle green leaves,

lush, tropical, jockeying for space, I wanted

camouflaging our wire-mesh fence, bending over

to whisper to me on my backyard stoop

I sat, toes furled in velvety St. Augustine

grass. I wanted fern, myrtle, laurel and malachite

the color of walrus tears on a rocky shore

in Maine, where I will go now to live amidst

coastal rocks covered with barnacles and moss.

Indeed, the speaker’s powerful voice owns both New York and Louisiana by the end of the collection. And it is in this, Banks plainspoken verse, that any reader can find the gumption to purchase and own his/her places, lovers, and houses.